A strategic enabler for the rail and telecoms industries to offer train passengers appropriate connectivity to use smartphones, tablets and laptops in the way they need and expect.

What is the problem to be solved?

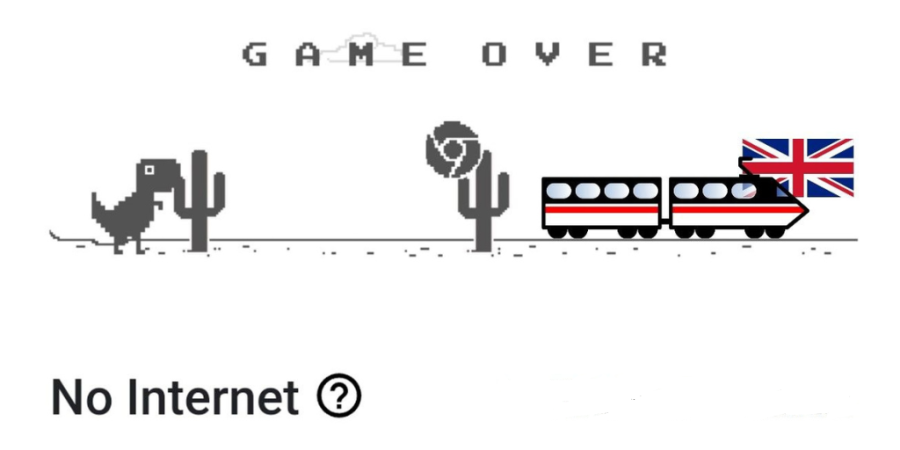

Those identifying as part of the rail industry frequently receive unsolicited train journey horror stories. It is rare that such well-intentioned and honest feedback doesn’t include comment on how poor their on-train voice and data (Internet) experience has been. As mobile device users,we have come to expect consistently good connectivity, both at-home and on our travels. The on-train experience now stands-out as Britain’s last great connectivity wilderness.

Despite on-train WiFi provision being relatively ubiquitous in the UK, poor passenger experience results from a failure to deliver an appropriate wireless, satellite or mobile connection between the train and terrestrial telecoms networks. A lack of structures investment to improve connectivity to trains can be attributed to ministers, policymakers, rail operators and connectivity providers having no evidence as to economic and societal benefits of connecting passengers.

What is the solution to the problem?

Directly serving users with an on-train network represents an efficient, reliable, scalable and future-proof means to resolving the current challenges to passenger connectivity. To date, this approach has been largely delivered as a WiFi service across much of Britain’s passenger train fleet. This approach does not preclude retrospective on-train deployment of small cells delivering native mobile connections for the mobile operators. But before envisaging any business or technology solution, it is proposed to undertake a three-phase programme or research:

Commercial model (Business Case)

There is currently little evidence of an attractive commercial model to enhance the ground to train connectivity necessary to deliver a satisfactory on-train train passenger connectivity experience in Britain beyond un-quantified returns to mobile operators achievable from best endeavours coverage of the railway from existing masts. All other track to train connectivity deployment and enhancement initiatives have been pilot deployments (Isle of Wight), local government enabled (Merseyrail) or those satisfying commitments made as part of the passenger franchising process (Avanti and EE on WCML). In many cases, costs and benefits (unknown) have fallen to different parties, making the challenge even greater.

Benefits

Improved railway trackside connectivity will only deliver limited benefit to the operation and management of the railway. RSSB’s 2012 report (Operational Communications - a programme of work to develop an effective strategy that supports rail innovation) looked at connectivity needs but failed to find any benefit case for improvement. From a current view, it appears that Britain’s railway is likely to be self-serving with its existing GSM-R network and its migration to 5G FRMCS during the 2030s. Usage will also be made of public 4G/5G mobile and satellite services where these exist, but the findings for the RSSB report indicate that incremental benefits from filling “not-spots” are unlikely to result in a positive business case.

Lessons Learnt

The list of positives is short and mainly limited to an acceptance that this has never been a technology-constrained problem. With the possible exception of needing to encourage the market to develop satellite antennas that are more physically suited to UK trains, there is no requirement to commission trials of novel technology or deployment methodologies. In-fact several credible and mature technology approaches to connecting the train to telecoms networks and the Internet can be evidenced:

- Radwin “fibre in motion” supporting WiFi on Merseyrail underground train services [track to train connectivity with high hundreds of Mbps throughput]

- Boldyn Networks multiple MNO service delivery on London Underground [“though the window” native 4G/5G mobile connectivity to passengers with aggregate throughput in the high hundreds of Mbps]

- Blu Wireless millimetric connection for Isle of Wight and South West Main Line trains [track to train connectivity with multiple Gbps throughput] along with international deployments for Caltrain on their Silicon Valley main line.

If you’re ready to embark on a connectivity project, we can point you to the suppliers with expertise in your sector.